The draft permits for the burning of biomedical waste in Bristol are getting attention. Mike Ewall, founder of the Energy Justice Network and noted environmental attorney, has provided BARC with an analysis and detailed recommendations in response to the draft permits.

Summary recommendations

- DEEP ought to require that Reworld (Covanta) abide by the federal standards for new medical waste incinerators.

- DEEP ought to require that Reworld meet the new EPA standards for Large Municipal Waste Combustors, which will take effect within the period of these new permits.

- DEEP ought to require that Covanta continuously monitor or continuously sample for mercury, hydrochloric acid, hydrofluoric acid, dioxins/furans, and PFAS.

Analysis and detailed recommendations

Recommendation 1

DEEP ought to require that Reworld (Covanta) abide by the federal standards for new medical waste incinerators.

The air permits are headed by the words “NEW SOURCE REVIEW PERMIT TO CONSTRUCT AND OPERATE A STATIONARY SOURCE.” As it pertains to medical waste incineration, this facility is indeed a new source. Emissions limits in federal regulations for new medical waste incinerators are far more stringent than for existing ones, and are also far more stringent than standards for municipal waste combustors (trash incinerators). Unfortunately, Reworld is exploiting a federal loophole that allows them to burn large quantities of medical waste without any of the requirements for medical waste incinerators applying to them.EPA describes this loophole in a draft frequently asked questions about the medical waste incineration regulations1:

2. Is there a reason why a state which has no HMIWI and only “large” municipal waste combustors (MWCs), which are exempt, should adopt the HMIWI EG?

Answer: Per §60.32e(e), only incinerators subject to the MWC rule for large MWCs (subparts Cb, Ea, or Eb) would be exempt from the HMIWI rule. If a state has no sources subject to the amended EG, then it would not need to submit a State Plan. However, the state may want to submit a State Plan in order to address the contingency that a source would bed is covered and the state wants the source to be subject to the specifics of a State Plan rather than deferring to the Federal Plan.

EPA’s webpage on Hospital, Medical, and Infectious Waste Incinerators (HMIWI) links to each of the three regulations below, which spell out this exemption:

Subpart Ce Emission Guidelines and Compliance Times for Hospital/Medical/Infectious Waste Incinerators

§ 60.32e Designated facilities.

(e) Any combustor which meets the applicability requirements under sub-part Cb, Ea, or Eb of this part (standards or guidelines for certain municipal waste combustors) is not subject to this subpart.2

Subpart Ec Standards of Performance for New Stationary Sources: Hospital/Medical/Infectious Waste Incinerators

§ 60.50c Applicability and delegation of authority.

(e) Any combustor which meets the applicability requirements under sub-part Cb, Ea, or Eb of this part (standards or guidelines for certain municipal waste combustors) is not subject to this subpart.3

Subpart HHH Federal Plan Requirements for Hospital/Medical/Infectious Waste Incinerators Constructed On Or Before December 1, 2008

§ 62.14400 Am I subject to this sub-part?

(b) The following exemptions apply:

(4) Own or operate a combustor which meets the applicability requirements of 40 CFR part 60 subpart Cb, Ea, or Eb (standards or guidelines for certain municipal waste combustors. …. Are not subject to this sub-part….”4

The federal regulations get confusing and perhaps contradictory about what percentage of medical waste can be burned while still remaining exempt from medical waste incinerator regulations. Section 60.32e(c) of the HMIWI regs exempts “cofired combustors,” which are defined in 60.51(c) this way:

Co-fired combustor means a unit combusting hospital waste and/or medical/infectious waste with other fuels or wastes (e.g., coal, municipal solid waste) and subject to an enforceable requirement limiting the unit to combusting a fuel feed stream, 10 percent or less of the weight of which is comprised, in aggregate, of hospital waste and medical/infectious waste as measured on a calendar quarter basis. For purposes of this definition, pathological waste, chemotherapeutic waste, and low-level radioactive waste are considered “other” wastes when calculating the percentage of hospital waste and medical/infectious waste combusted.” (emphasis added)

This provision is clearly intended to cover units burning “municipal solid waste” and to make clear that only units that have an enforceable requirement that limits them to burning 10% medical waste or less get out of HMIWI regs. However, section 60.32e(e) provides “Any combustor which meets the applicability requirements under subpart Cb, Ea, or Eb of this part (standards or guidelines for certain municipal waste combustors) is not subject to this subpart.” The applicability requirements in those MWC subparts (Cb, Ea, and Eb) don’t exclude HMIWI.

They do exclude “cofired combustors,” which are defined for the MWC regs (as opposed the HMIWI regs) as units “combusting municipal solid waste with nonmunicipal solid waste fuel (e.g., coal, industrial process waste) and subject to a federally enforceable permit limiting the unit to combusting a fuel feed stream, 30 percent or less of the weight of which is comprised, in aggregate, of municipal solid waste as measured on a calendar quarter basis” (emphasis added). If a unit has a federally enforceable permit allowing it to combust no more than 30% municipal waste, it’s a cofired combustor under the MWC regulations. That means the MWC regulations don’t apply to it, the exception for MWC in the HMIWI regulations (at 60.32e(e) doesn’t apply either, and the unit is subject to the HMIWI regs. But if the unit doesn’t have such a federally enforceable permit, it can burn 99% medical waste and still be a MWC under EPA’s regs.

So, why would the HMIWI regs exempt only MWC that are limited to burning less than 10% medical waste and then, two provisions further down, exempt all MWC (unless they’re limited to burning less than 30% municipal waste)? The second provision makes the first one virtually meaningless, at least with respect to MWC that choose to burn medical waste.

Reworld has a trash incinerator burning medical waste in Marion County, Oregon. Oregon DEQ’s Air Quality Administrator, Ali Mirzakhalili, admitted that even if Covanta started burning 100% medical waste, they would not be subject to medical waste incinerator regulations because they were initially classified as a municipal waste combustor. He told me in a meeting that he has consulted EPA on this, and he admits that it’s a “head scratcher” that does not make sense.

DEEP can close this loophole. The Clean Air Act contains a savings clause at 42 U.S.C. § 7416 which allows states and their political subdivisions to have stricter air pollution laws than the federal floor:

§ 7416. Retention of State authority

Except as otherwise provided in sections 119(c), (e), and (f) (as in effect before the date of the enactment of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977), 209, 211(c)(4), and 233 (preempting certain State regulation of moving sources) nothing in this Act shall preclude or deny the right of any State or political subdivision thereof to adopt or enforce (1) any standard or limitation respecting emissions of air pollutants or (2) any requirement respecting control or abatement of air pollution; except that if an emission standard or limitation is in effect under an applicable implementation plan or under section 111 or 112, such State or political subdivision may not adopt or enforce any emission standard or limitation which is less stringent than the standard or limitation under such plan or section.

This authority clears the way for DEEP to close the federal loophole and hold Reworld to the standards for what they seek to do: start a new operation as a medical waste incinerator.

It is clear that Reworld cannot meet the standards for a new medical waste incinerator without improving on their pollution controls. It is self-evident in the fact that medical waste incinerator regulations are more stringent than those for trash incinerators (municipal waste combustors) that burning medical waste is a more dangerous activity warranting more stringent emissions controls.

Reworld operates three other trash incinerators that currently burn medical waste. They are their trash incinerators in Marion County, Oregon, Lake County, Florida, and Huntsville, Alabama. They are also currently seeking to start burning medical waste at their Tulsa, Oklahoma trash incinerator.

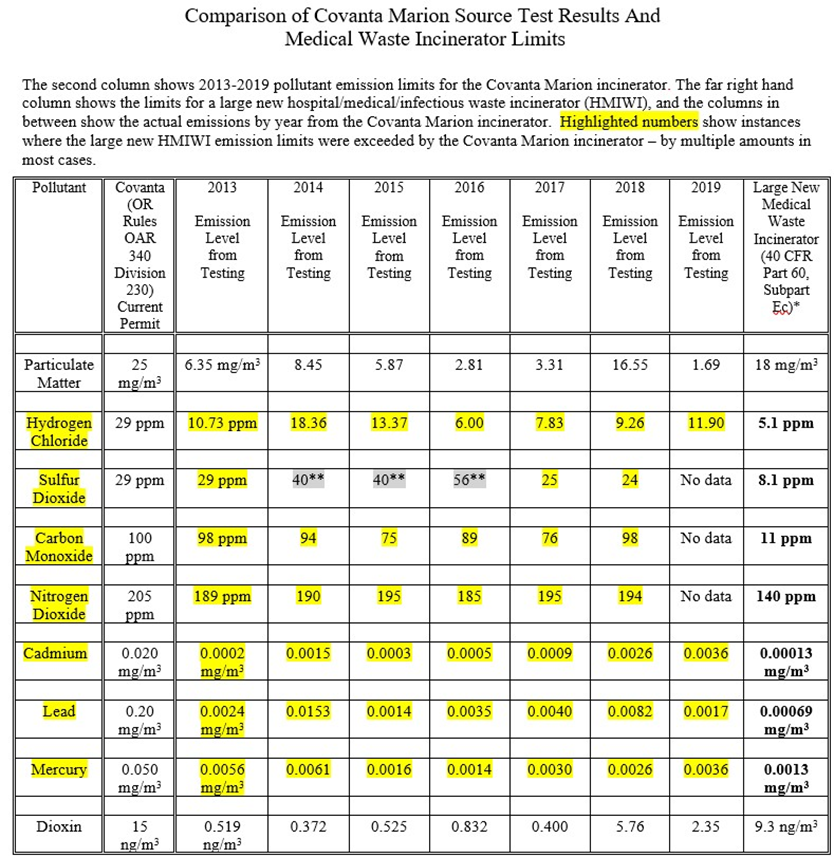

The follow chart shows how the Marion County incinerator is unable to meet the medical waste regs:

Covanta Bristol is in a similar boat, unable to meet the requirements new medical waste incinerators unless they improve their pollution controls. Values in red exceed the requirements.

| Covanta Bristol | ||||

| Pollutant | Units | Large New Medical Waste Incinerators | Federal standards for older (existing) trash incinerators | 2018-2020 average |

| Particulate Matter | mg/m3 | 18 | 25 | 2 |

| Hydrogen Chloride | ppm | 5.1 | 29 | 5 |

| Sulfur Dioxide | ppm | 8.1 | 29 | 13.4 |

| Carbon Monoxide | ppm | 11 | 100 | 20.4 |

| Nitrogen Dioxide | ppm | 140 | 205 | 128.4 |

| Cadmium | μg/m3 | 0.13 | 35 | 2.4 |

| Lead | μg/m3 | 0.69 | 400 | 18.8 |

| Mercury | μg/m3 | 1.3 | 50 | 1 |

| Dioxin | ng/m3 | 9.3 | 30 | 2.5 |

Our analysis of emissions from Reworld’s Lake County, Florida medical waste-burning trash incinerator shows that they exceed the new medical waste incinerator regulations for hydrochloric acid, carbon monoxide, mercury, and cadmium most of the time, and exceed the limits for nitrogen oxides and lead all of the time in the data we examined from 2001 through 2022 for both units. They started burning medical waste in September 2018.

Our analysis of emissions from Reworld’s Huntsville, Alabama medical waste-burning trash incinerator shows that they exceed the new medical waste incinerator regulations for hydrochloric acid and cadmium most of the time, nitrogen oxides and lead all of the time, and mercury and carbon monoxide some of the time in the data we examined from 2008 through 2020 for both units. They started burning medical waste in June 2016.

The sheer tonnage Reworld seeks to burn would place their Bristol incinerator as the third or fourth largest medical waste incinerator in the nation, following the dedicated medical waste incinerators in Baltimore, Maryland and Anahuac, Texas, and perhaps also following their Huntsville, Alabama trash incinerator that burns medical waste. Given this size, it makes sense that they compete fairly and be held to the standards of a large new medical waste incinerator. DEEP has the authority to hold them to this standard, and ought to do so.

Recommendation 2

DEEP ought to require that Reworld meet the new EPA standards for Large Municipal Waste Combustors, which will take effect within the period of these new permits.

EPA is nearly 20 years overdue in updating standards for large municipal waste combustors (LMWCs).5 These regulations are nearly finalized and should be in effect by 2028-2029, within the time frame of the permits being issued. DEEP should ensure that the stricter requirements of these federal regulations are incorporated as part of these permits.

Recommendation 3

DEEP ought to require that Covanta continuously monitor or continuously sample for mercury, hydrochloric acid, hydrofluoric acid, dioxins/furans, and PFAS.

Covanta promised, in their communications with environmental stakeholders and the public while seeking these permits, that they would use continuous emissions monitors for mercury if they start burning medical waste. This is not reflected in the draft permits and ought to be, along with other continuous monitoring requirements that are relevant to this sort of waste stream.

Medical waste can contain mercury devices and perhaps even mercury from dental amalgam fillings, as dental offices and funeral homes are among the sources listed in the solid waste permit under the definition of a “generator of biomedical waste.” Medical waste also contains substantial amounts of plastic, which includes polyvinylchloride (PVC) plastics and plastics containing PFAS. PVC plastic is halogenated with chlorine. This and other halogenated compounds, including pharmaceuticals, produce hydrochloric acid, hydrofluoric acid, and dioxins/furans when burned. PFAS, used in many products including fire-fighting foam because it doesn’t burn, has been shown to be able to survive incineration intact and be emitted by waste incinerators.

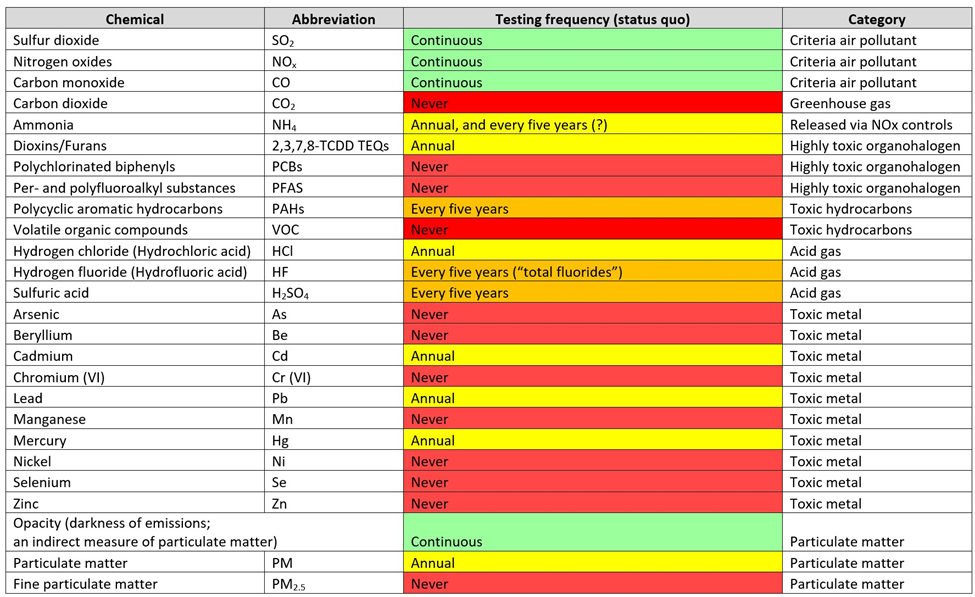

WHY CONTINUOUS MONITORING?

With the exception of a few pollutants (nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide), other chemicals are required to be tested just once per year, if at all. In this permit, it’s weaker than most, allowing some chemicals to be tested just once every five years. See the following chart for a more visual take on the testing requirements in this permit:

This is a weaker testing regime than found at most trash incinerators. If we regulated motorists the way we do most pollutants tested in this permit, it would be akin to enforcing a speed limit by allowing drivers to drive all year with no speedometer. Once a year, a speed trap would be set on the highway with signs warning “slow down… speed trap ahead,” and the driver’s brother would be running the speed trap (companies choose who they pay to conduct the test).

Lest you forget, this is the same company that, at their Preston incinerator, has been fined by the Connecticut Attorney General in 1993 for tampering with their continuous emissions monitors to make it seem that their emissions were lower than they really were.6 In Tulsa, Oklahoma in 2013, Covanta (now Reworld) was the target of a criminal investigation by the U.S. Attorney’s Office “related to alleged improprieties in the recording and reporting of emissions data” in which Covanta entered into a nonprosecution agreement to follow applicable laws and regulations and pay a $200,000 “community service payment” to the state environmental agency.7

It’s clear that this company cannot be trusted to monitor themselves properly without independent enforcement. In fact, we have heard from workers at other plants that this company has a habit of manipulating annual stack tests by stockpiling waste that burns cleaner, like cardboard, to burn on their testing day, even though this is not representative of what they typically burn.

UNDERESTIMATING POLLUTION

Testing just once a year underestimates actual pollution levels. An analysis of seven years of data from the nation’s largest trash incinerator, Covanta Delaware Valley in the City of Chester, Pennsylvania, where they monitor hydrochloric acid continuously as well as once per year in an annual stack test, the continuous monitors show actual emissions to be 62% higher than annual stack tests show.

Increased downtime at aging incinerators results in higher emissions from startup and shutdown occurrences. Dioxin emissions are a stark example. One study out of Europe found that using continuous sampling for dioxins at incinerators found the actual emissions to be 32-52 times higher than we think they are in the U.S. when requiring incinerators to test each unit just once per year under ideal operating conditions.8 A more recent study found that our failure to use continuous sampling technology is underestimating dioxin emissions by 460 to 1,290 times.9

Continuous sampling for dioxins/furans at Covanta’s Durham York Energy Centre in Ontario has also shown higher emissions than their stack tests indicate, sometimes over 30 times higher, and probably far higher in the many other results they will not release because they have dismissed them as “invalidated” due to various operating conditions that would increase dioxin emissions. It’s well known that dioxin emissions are very temperature-sensitive and can spike during startup, shutdown, and malfunction conditions – precisely when stack testing is not done.

Considering that continuous sampling technology has been tested and verified by EPA since 200610 and that dioxin is the most toxic substance known to EPA – 140,000 times more toxic than mercury11 – there is no excuse for not requiring continuous dioxin sampling at waste incinerators. According to a 2012 Envirotech article:

“In 2010 France followed the example of Belgium and demanded, by law, the continuous sampling of PCDD/PCDF emissions in all domestic and hazardous waste incineration plants until the 1st of July 2014. This law covers around 200 stacks,which will increase the total number of worldwide installed continuous dioxin monitoring systems to around 450 to 500 systems.”12

While genuinely continuous emissions monitors for dioxins/furans and PFAS are not commercially available (though at least one has been tested and verified by EPA in 2006), the technology to continuously sample them has been used for over 25 years, as referenced above. The most common type is known as AMESA.13,14 This samplers collect a sample for up to 4-6 weeks and the sample cartridge can then be switched out and replaced, and sent to a lab for testing.

Here are three companies that currently provide dioxin/furan continuous sampling technology in the U.S.:

For PFAS continuous sampling, see PFAS in Air: Sampling and Analytical Techniques for the Identification of Persistent Contaminants.

Similarly, the technology to continuously monitor mercury and hydrochloric acid is well established. In Pennsylvania, all six trash incinerators use continuous emissions monitoring for hydrochloric acid, some for over 20 years now.15

In addition to widespread use of mercury continuous emissions monitors, a multi-metals CEM is available that can test many metals at once. Oregon-based Cooper Environmental (now SailBri Cooper) makes the multi-metals continuous emissions monitor that provides on-site results within an hour of a one-hour sample collected, so that every hour, data is available for the prior 60-120 minute period. See Xact 640 at https://sci-monitoring.com/product/xact-640-multi-metals-monitor/

WHERE ARE CONTINUOUS MONITORS USED AT INCINERATORS?

- Hydrochloric acid: all six trash incinerators in Pennsylvania, plus Covanta’s Union and Camden County incinerators in New Jersey, Covanta Onondaga in New York, Covanta’s Durham-York Energy Centre in Ontario, Canada, and the (now closed as of June 2024) Wheelabrator Portsmouth incinerator in Virginia.

- Hydrofluoric acid: Covanta’s Durham-York Energy Centre in Ontario, Canada.

- Ammonia: The Union County, NJ incinerator, and Covanta’s Huntington and Onondaga incinerators in New York, and Covanta’s Durham-York Energy Centre in Ontario, Canada continuously monitor for ammonia.

- Dioxins/furans, PCBs, and toxic metals: Covanta Marion in Oregon, since the passage of Senate Bill 488 in 2023, will have to continuously monitor for nine toxic metals and should be continuously sampling for dioxins/furans and PCBs under state law, but plans to evade that legal requirement.

- Dioxins, mercury, and particulate matter: According to Covanta’s website about their innovations, they claim the following about their Covanta Haverhill incinerator in Massachusetts: “2010: Another first in the U.S., Covanta Haverhill serves as a beta test site for the installation and demonstration of a new continuous monitoring system for mercury, dioxin and particulate matter. Although the dioxin monitor still requires laboratory analysis, it allows long-term monitoring of emissions without a team of specialists. Data gathered explains the relationship between operations and emissions so facilities can consistently drive emissions toward zero.”

- Mercury: West Palm Beach #2 in Florida tested mercury CEMS from 2015-2018, as did Covanta’s Hillsborough County, Florida incinerator (at Unit #4 from 2009-2015). Durham-York Energy Centre operated by Covanta in Ontario, Canada, and Covanta Onondaga in New York, may also have mercury CEMS.

- Dioxins/furans: Durham-York Energy Centre in Ontario, Canada is another incinerator using long-term sampling for dioxins/furans.

HOW SHOULD CONTINUOUS MONITORTING BE IMPLEMENTED?

DEEP should require that continuous sampling (such as AMESA) be used for dioxins/furans and PFAS, and that truly continuous emissions monitoring of mercury (if not other metals using the multi-metals CEM) as well as hydrochloric acid and hydrofluoric acid. This data should be made available real-time on a public website as Reworld/Covanta already does for other pollutants at many of their incinerators.

This continuous monitoring data should be used for compliance once DEEP affirms that the data is reliable for that purpose and one performance standards are established by EPA or DEEP.

DEEP should only allow Reworld to burn medical waste in one of their two burners, but should require the continuous monitoring/sampling on both burners so that the two units can be compared to one another. Stack tests should be conducted as usual as well as using the continuous monitoring, and estimates of annual emissions should be produced from both test methods so that they can be compared, affirming whether continuous testing shows that emissions are higher, in reality, than annual stack tests under optimal operating conditions indicate.

Finally, the provisions allowing unusual operating conditions during a stack test, such as lifting all limits on carbon injection rates when testing for pollutants like dioxins and mercury that are controlled using carbon injection, must be removed from the permit. Tests should best approximate actual operating conditions, not idealized operating conditions.

Footnotes

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-01/documents/hmiwifaq_7-18-11_faq.pdf#page=10 ↩︎

- https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2015-title40-vol7/pdf/CFR-2015-title40-vol7-part60-subpartCe.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2015-title40-vol7/pdf/CFR-2015-title40-vol7-part60-subpartEc.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2015-title40-vol9/pdf/CFR-2015-title40-vol9-part62-subpartHHH.pdf ↩︎

- https://www.epa.gov/stationary-sources-air-pollution/large-municipal-waste-combustors-lmwc-new-sourceperformance ↩︎

- Covanta was fined $20,000 in 1993 in a civil action filed by the Connecticut Attorney General in response to an employee adjusting a continuous emissions monitoring device to alter a reading in order to pass a continuous emissions monitoring audit. See page 37 for this 1993 incident reported in this 93-page compilation of Covanta’s U.S. violations through September 2006: www.energyjustice.net/files/incineration/covanta/violations2006.pdf ↩︎

- See Covanta Holding Corporation’s 2019 10-K Securities and Exchange Commission filing, p. 105. (see “Tulsa Matter” describing the consequences of this 2013 incident) d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0000225648/992dfb7f-398d-4b178e33-75e956f6f235.pdf ↩︎

- De Fré R, Wevers M. “Underestimation in dioxin emission inventories,” Organohalogen Compounds, 36: 17–20. www.ejnet.org/toxics/cems/1998_DeFre_OrgComp98_Underest_Dioxin_Em_Inv_Amesa.pdf ↩︎

- Arkenbout, A, Olie K, Esbensen, KH. “Emission regimes of POPs of a Dutch incinerator: regulated, measured and hidden issues.” docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/8b2c54_8842250015574805aeb13a18479226fc.pdf ↩︎

- Environmental Protection Agency, Environmental Technology Verification Program. https://archive.epa.gov/nrmrl/archiveetv/web/html/vt-ams.html#dems ↩︎

- Environmental Protection Agency, Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (RSEI) Model. www.epa.gov/rsei ↩︎

- “15 Years Continuous Emission Monitoring of Dioxins Experiences and Trends,” AET April/May 2012. https://www.envirotech-online.com/article/environmental-laboratory/7/environnement-sa/15-years-continuousnbspemissionmonitoring-of-dioxins-experiences-and-trendsnbsp-nbsp/1187 ↩︎

- Adsorption Method for Sampling of Dioxins and Furans (AMESA): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adsorption_Method_for_Sampling_of_Dioxins_and_Furans ↩︎

- https://www3.epa.gov/ttnemc01/meetnw/2002/riley_am.pdf ↩︎

- https://files.dep.state.pa.us/Air/AirQuality/AQPortalFiles/Business%20Topics/Continuous%20Emission%20Monitoring/ docs/CEMS_ApprovedPending_ExternalWeb.pdf ↩︎